Camino Del Diablo, AZ

THE DEVIL’S HIGHWAY

In Search of Drug Smugglers and Unexploded Ordnances

Author: Gary Wescott / Photos: Gary and Monika Wescott

It isn’t often that we find an adventure as tempting as Arizona’s Devil’s Highway, otherwise known as “El Camino Del Diablo”, who could resist a name like that. Paging through the Backcountry Adventures of Arizona guidebook, published by Alder Backcountry Guides, we found the trailhead off I-80 just outside of Yuma. That was convenient. Since we were headed to the Overland Expo 2010, why not do a little Overlanding on the way. The Devil’s Highway was given a “Difficulty Rating” of 4, so we figured The Turtle V would not have a problem.

It isn’t often that we find an adventure as tempting as Arizona’s Devil’s Highway, otherwise known as “El Camino Del Diablo”, who could resist a name like that. Paging through the Backcountry Adventures of Arizona guidebook, published by Alder Backcountry Guides, we found the trailhead off I-80 just outside of Yuma. That was convenient. Since we were headed to the Overland Expo 2010, why not do a little Overlanding on the way. The Devil’s Highway was given a “Difficulty Rating” of 4, so we figured The Turtle V would not have a problem.

The 130 miles of remote dirt tracks lead through the 2 million-acre air-to-ground and air-to-air Barry M. Goldwater Air Force training range, (third largest land-based military range in the U.S.), the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Area, (the third largest in the lower 48 states), and the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, all in close proximity to the Mexican border. Never mind that they don’t recommend you drive this route alone.

We did need a permit to traverse all three of these protected areas, but despite what some sources advised, we only needed one that covered all three. We picked that up at the Marine Corp Air Station (928 269-7150), just off Hwy 80. The map they supplied with our permit, (last updated in 2008), gave trail markers.

With a “Difficulty Rating” of 4, we aired down our big XZLs to 35 psi and headed east on a washboard-graded road.

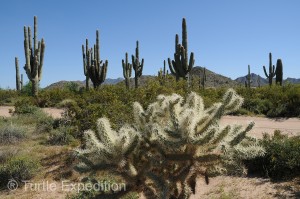

Arriving at the end of the pavement, we aired down our big XZLs to 35 psi and headed east on a washboard-graded road across a wide valley below the Gila Mountains. This was a drive in the country so far. Flaming Ocotillo flags gave color to the desert. Concentrations of spiny Teddybear Cholla and signs warning DANGER–LASER IN USE–DO NOT ENTER kept us from even thinking of wandering off the road. Unexploded ordnances were not something we wanted to find. At least we didn’t have the problems of thirst or exposure faced by early Spanish explorers and missionaries using the trail as a short cut to California. More than 2,000 souls could be buried in the desert, victims of what has earned El Camino Del Diablo a reputation of being the most deadly of immigration trails. The number grows today as illegal immigrants and drug smugglers attempt to sneak into the U.S. across the unfenced border.

A setting sun across the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force training range brought a silence you could touch.

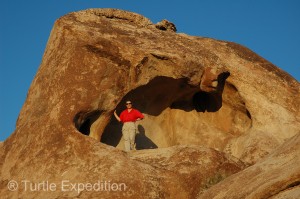

A couple of hours took us past the A8 marker, a faint trail to Spook Canyon, and south to the tip of Vopoki Ridge. Strange rock formations resembling melting wax in the setting sun prompted us to find a camp. The silence was amazing. In the clear desert air the stars seemed within arms’ reach. (32° 26’ 23” N, 114° 15’ 58” W)

A couple of hours took us past the A8 marker, a faint trail to Spook Canyon, and south to the tip of Vopoki Ridge. Strange rock formations resembling melting wax in the setting sun prompted us to find a camp. The silence was amazing. In the clear desert air the stars seemed within arms’ reach. (32° 26’ 23” N, 114° 15’ 58” W)

Morning was cool enough to build a little fire in an existing pit. There was plenty of down wood, and the ridge behind us gave an extra couple of hours of shade as we watched the sun slowly burn across the desert in front of us. It was the beginning of a mild April day, but heat waves gave a clear sign of what summer could bring.

Strange rock formations resembling melting wax in the setting sun, prompted us to find a camp near the tip of Vopoki Ridge.

The Route Description in our Alder Backcountry Guide gave us a wash-by-wash, sidetrack-by-sidetrack, mile-by-tenth of a mile log. Using our Lowrance iFinder 500 as a trip meter, we quickly saw the mileages were not always accurate, but the GPS coordinates were right on. Particularly in the Goldwater Range, we were instructed to stay on the main road at all times. It was sort of like being on a train. We knew where we were, but there was really no choice. Sit back and enjoy the scenery. There was plenty of that. Thanks to late rains, nearly every flower and cactus was in full bloom. We explored a side trail at the A9 marker leading up the backside of Vopoki Ridge on the edge of the Davis Plain. There were some nice campsites and a colorful display of Ocotillo and brilliant Brittlebush.

Our GPS gave us a warm fuzzy feeling when nothing else matched. We did not want to find any unexploded ordnances.

The graded road was rapidly becoming more of a two-track, and a few deep washes added some interest. We stayed in two-wheel drive, letting our long wheelbase walk us through. With the low-end torque of our Power Stroke, augmented by the new ATS Aurora 3000 turbo we had recently installed, we didn’t even shift into low range. There were a couple of spots that might encourage a small SUV to turn around. We wondered if this was the start of the “Class 4” rating. We veered left to climb over Tinajas Altas Pass. Numbers on military marker posts seem to have changed, and mileages seemed to vary significantly, so our GPS gave us a warm fuzzy feeling when nothing else matched. We were still not looking for unexploded ordnances.

Things got a little weird around marker A15, A16,–or was it A16a. There was an unmarked triangle that was missing signs. One road went northwest, following Camino Del Diablo Este (east). We had been following Camino Del Diablo Oeste (west). (Yeah, there are two main trails.) What we were looking for was the unmarked track to the Tinajas Altas or “High Tanks”. Called Agua Escondido, “hidden water”, by Padre Kino, they are a string of nine natural rock basins running up a cliff in the Tinajas Altas Range. When full, they can hold 20,000 gallons of precious water. Often the lower pools are dry, and the upper tanks are only reached by a difficult and dangerously steep climb. Many died being too weak to reach them, or falling to their death in an attempt.

On a long walk up a dry wash near our second camp, we could still keep an eye on our truck in the distance.

At length, we found a sign pointing down some well-used ruts to a turn-around, .9 miles. A 10-minute hike brought us to the lower tinaja. It was half full of stagnant tea-colored water. Nothing you would want to drink. On the other hand, 200 years ago, this was the only water source for perhaps a hundred miles. If you were exhausted from the 110° heat and had been without water for two days, this would have looked like a cold bottle of Perrier or an icy Corona. (Sorry, no lime.) (Tip: Cross the wash, take the first path to the left and the second path to the right.)

Backtracking to the ambiguous junction, we took the most obvious road southeast and soon entered the Cabeza Prieta Refuge. A couple of Border Patrol trucks stopped at the entrance parking area to check on their passengers, half a dozen illegal immigrants who had snuck across the border. We began to see the stately, sometimes humorous, Saguaro cacti.

This area is closed to the public from March 12 to July to protect the endangered Sonoran Pronghorn, unless otherwise adjusted. They must be endangered, because we never saw one. There are over 300 kinds of wildlife calling this parched land home, including 24 species of snakes, six of which are rattlers. Over 90% of the refuge is designated Wilderness Area. Vehicles may park and camp up to 50 feet from the main road in areas previously used by others.

Much of the sandy sections had been “graded” using a strange contraption of seven tires chained together and drug behind a Border Patrol pick-up.

Long sections of soft sand prompted us to stop and lock the hubs, but lowered tire pressure was enough to continue in two-wheel drive. We like to keep 4X4 as an option. If you get stuck, you can almost always flip a lever and back up to assess the situation. If you’re already in 4X4 mode, you have a problem. Much of the sandy sections had been “graded” using a strange contraption of seven tires chained together and drug behind a Border Patrol pick-up. We assumed the smooth, untracked surface would make it easy to spot illegal foot traffic. To our advantage, it also leveled much of the washboard.

About eleven miles from the entrance to the Cabeza Prieta Refuge we saw an unmarked trail lined with rocks on both sides. It looked like the entrance to a campground or something important. We followed a graded road that shortly turned into several washouts requiring 4X4 and low range to crawl through. After a little over a mile, our GPS map clearly showed we were driving straight toward the Mexican border. We backtracked and made a quick stop at Tule Wells to sign the guest book.

About eleven miles from the entrance to the Cabeza Prieta Refuge we saw an unmarked trail lined with rocks on both sides. It looked like the entrance to a campground or something important. We followed a graded road that shortly turned into several washouts requiring 4X4 and low range to crawl through. After a little over a mile, our GPS map clearly showed we were driving straight toward the Mexican border. We backtracked and made a quick stop at Tule Wells to sign the guest book.

Bumping over a low rocky pass, we found what we were looking for 4.3 miles from Tule Wells. Just as we stopped, a Border Patrol flashed his lights behind us. Apparently the little side road we had explored earlier was a known drug running route. The officer had seen the unusual tracks of our Michelin XZLs, and was sure we were smugglers. We all had a good laugh. The next morning, after a long walk up a dry wash and through fields of wild flowers stretching into the nearby hills, we didn’t get started until after 11:00. This camp was so peaceful, we wish we could have stayed a week.

Near Tule Wells we entered a section of soft sand, deep mud ruts, and bull dust. The braided tracks would not be passable after a heavy rain.

Twenty-one miles from Tule Wells we entered a section of sand, deep mud ruts, and bull dust. Clearly, the braided tracks would not be passable after a heavy rain. For several miles the trail wound through the desert like a coyote chasing a rabbit. Perhaps part of the original historic trail, it seemed to be made by someone on foot or horseback, following the best path through the Cholla and Ocotillo. In other areas, the road was so eroded, vertical sidewalls were over three feet high. It was like driving down a bobsled run through soft sand. It was the kind of road you wanted to turn around and drive again, but it was so narrow, it would have been difficult to do so.

We crept over a rocky five miles across the Pinacate Lava Flow and back into more bull dust. Mesquite trees racked the sides of the truck. Having been forewarned that there were narrow brushy sections, we had taken the precaution of covering our Seitz windows and the lower half of the truck and camper with 3M Removable Paint Protection Film. This easy to apply product can do wonders to keep the gouging mesquite needles out of your truck’s paint job.

We crept over a rocky five miles across the Pinacate Lava Flow and back into more bull dust. Mesquite trees racked the sides of the truck. Having been forewarned that there were narrow brushy sections, we had taken the precaution of covering our Seitz windows and the lower half of the truck and camper with 3M Removable Paint Protection Film. This easy to apply product can do wonders to keep the gouging mesquite needles out of your truck’s paint job.

The old grave site of a prospector named Dave O’Neills was one of hundreds, maybe thousands, along this trail.

Passing the gravesite of Dave O’Neills, a prospector who died from exposure and dehydration, we came to the huge Border Patrol station, not shown on any maps. A little further on, the Papago Well and tank made a good lunch stop, and there was water, despite repeated warnings that “there is no water anywhere on the route”. The sand was deeper now. We could hear the pitch of the engine change in the soft spots. Apparently it gets even worse in the heat of the summer. One section was “paved” with interlocking steel aircraft landing mats.

We had taken the precaution of covering our Seitz windows and the lower half of the truck and camper with 3M Removable Paint Protection Film.

As we passed into the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, the desert was progressively greener. Bates Well was our last stop. Abandoned now, the Border Patrol has a 6X6 flatbed parked at the entrance for a refueling station. From here it was an easy 15 miles to the blacktop of Hwy 85 where we aired up and peeled off the 3M Protective Film, which had limited the damage to a few minor pinstripes. In three days, we had seen fewer than ten vehicles, and most of them were friendly Border Patrol. No animals. No illegal immigrants. No drug smugglers. No unexploded ordnances.

Ajo to the north held little of interest, and Lukeville to the south even less. We headed for the convenience of the scenic Twin Peaks Campground inside the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Snowbirds were already packing up their big RVs and heading north with the geese.

El Camino Del Diablo is a beautiful route. If you time it right, (about six weeks after the rain), the flowers can be as spectacular as the silence. A full-size Ford should have no problem on this mini adventure, but do go equipped for the worst, with plenty of fuel, water, and necessary equipment for backroad travel.

Other Sources:

Other Sources:

Bureau of Land Management

Yuma Field Office

928 317-3200

www.blm.gov/az/st/en/fo/yuma_field_office.html