China # 4 – Crossing the Taklamakan Desert – September 2014

Three hundred and thirty seven thousand square kilometers, (130,000 sq. mi), The Taklamakan is one of the largest sandy deserts in the world and one of the most dangerous. Nicknamed “The Sea of Death”, one translation in Chinese is, “If you go in, you won’t come out.”

Flanked by the high Tien Shan Mountains to the north, the Kunlun Mountains to the south, the Pamirs to the west and the daunting Gobi Desert on the east severely restricted access to a region that was already extremely hazardous to traverse. With a length of 1,000 kilometers, (620 miles), and a width of 400 kilometers (250 miles), it was a major obstacle for caravans along the Silk Road. Lisa, our trip planner at Navo-Tour, was surprised that we insisted on crossing it.

Taklamakan Desert, the Sea of Death

Its larger sand-dune chains range from 100 to 500 feet (30 to 150 meters) in height, while its pyramidal dunes rise 650 to 1,000 feet (200 to 300 meters). Needless to say, no one in their right mind would attempt to cross this waterless desert with a string of camels. Caravans had to go around it. In the 1950s, oil was discovered in the north and even greater deposits were found in the 1980s along the southern rim, which is where we turned north off the “Southern Silk Route” (Hwy 315). Our plan was to drive across the center to Luntai where we could pick up the “Northern Silk Route”. Our map showed a secondary oil exploration road that would traverse the desert at one of its widest points. Even with altitudes ranging from 3,900 to 4,900 feet above sea level, daytime temperatures can still exceed 100°F, and unless you are a lizard there is not a lot of shade.

- The sand dune scenery was ever changing.

- We all had fun walking on the soft sand in the middle of our Taklamakan Desert crossing and couldn’t resist taking lots of photos.

- The different tracks in the sand led to speculations of what animal created them.

As we headed across, the landscape was flat and barren. A stream disappeared into the ground. Drifting sand was a major problem. Artificial sand breaks were built out of reeds stuck into the sand and an extensive drip irrigation system kept a row of tamarisk and nitre bushes alive along the edge of the blacktop. The occasional hummock in the sand dunes formed around a struggling tree or scrub. Soon there was only endless sand, but it was spectacular in its diverse shapes and colors. Strange outcroppings of clay or sand stone surfaced occasionally, possibly formed during the Cenozoic age about 655 million years ago. We saw no wildlife of any kind, only the funny tracks of lizards, snakes and mice. Depending on the texture of the sand and the direction of the wind, the surface was constantly changing.

The original idea was to spend a night in the middle of the desert, but the soft fine almost powdery sand was no place to set up Green’s tent. To our surprise, we came to the small settlement of Tachong midway with a gas station and a bunch of run-down hotels “servicing” the nearby oil exploration sites employees. No place for Green to stay safely. We asked permission to camp for the night on the edge of the gas station pad and we all relaxed in the cool of the evening. I was reminded of a famous saying by Carl Franz, author of People’s Guide to Mexico, “Wherever you go, there you are!”

In the morning we got an early start, which for us means maybe 9:00. As we got closer to Luntai vegetation increased and a grove of suffering sand blown Euphrates Poplar made a good lunch stop. We soon came to our first military checkpoint and Green convinced them that she really was a guide. She had to dig out her official papers.

Our wonderful guide, Green, was happy to have crossed the infamous Taklamakan Desert. She had never been here before.

Tensions between Han Chinese authorities, (the majority of the population), and the Hui minority people, (Muslim), natives to the Taklamakan, have existed for centuries. Han Chinese migration into the region, coupled with Islamic fundamentalist agitation elsewhere in Asia and minority unrest across the border in the Central Asian Republics, has fostered more open hostility by local peoples against the (Han) Chinese.

Just after we joined the “Northern Silk Road”, (Hwy 314), we spotted a deserted workers’ camp and truck stop. It was a perfect place to spend the night. There was even an irrigation ditch that gave us a chance to replenish our water supply, one bucket at a time. Monika and Green did a quick laundry and we studied our route to Turpan and the Gaochang Gucheng ruins. Gaochang Gucheng had been a busy trading center in the 1st century BC and it was an important stopping point for merchant caravans traveling on the Silk Road.

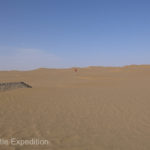

- Taking the turn-off from the “Southern Silk Road”, (Hwy 315), the land was barren and dead flat.

- This abandoned gas station at the entranced to the Taklamakan Desert made a good shady place for lunch.

- One of Green’s requests was to have a hot lunch.

- Artificial sand breaks were built out of reeds stuck into the sand.

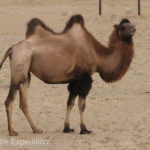

- Wild camels roamed close to the road. Their ancestors once caravanned along the Silk Road.

- It was 530 km to somewhere. This was the entrance to the desert crossing.

- This stream disappeared into the sand.

- The occasional hummock in the sand dunes formed around a struggling bush or dwarf tree.

- Trying to get a feeling for the immenseness of this desert, Gary trudged to the top of a sand dune. It was beyond imagination.

- If you look closely, you can spot Gary on the horizon.

- Gary walked quite far in this soft sand to take more photos.

- Green and Monika took a closer look at the extensive drip irrigation system that kept a row of tamarisk and nitre bushes alive along the edge of the blacktop.

- As far as the eye could see there was only impassible sand. Walking on it I would sometimes sink past my ankle, like walking on deep snow.

- The view to the front and the view to the back did not change for hours.

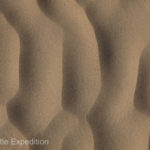

- Depending on the texture of the sand and the direction of the wind, the surface was constantly changing.

- We saw no wildlife of any kind, only the funny tracks of lizards, snakes and mice.

- In some places the sand was so fine, almost powder, the vibration of our footsteps would start miniature avalanches.

- Firm enough to drive on but not for very far. The texture and depth were constantly changing. We did not venture far from the blacktop.

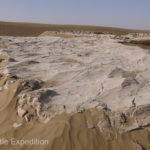

- These outcroppings of clay or sand stone were possibly formed during the Cenozoic age about 655 million years ago.

- As the afternoon light changed, shadows flowed across the endless sand dunes like a moving water color.

- A slight turn in the road only showed more of the same in the far distant horizon.

- A friendly gas station in the middle of the desert was unexpected and a good place to camp for the night.

- Hummocks like this one seemed to pop out from nowhere, a place for a bush to find water?

- As we neared the Talimu He river crossing we found welcome shade under some Euphrates Poplar trees.

- The Euphrates Poplar or Desert Poplar (Populus Euphratica) are the oldest poplars in the world.

- This is an Euphrates Poplar leaf.

- The Talimu He river near Luntai brought life to the “Sea of Death”.

- Local farm workers on their way home via rapid transit.

- It was melon season here.

- The melons were ripe and sweet, just picked from the fields.

- This vendor was happy to cut the melons into bite size for us to snack on.

- Our first of many military checks. Green had to explain (and show her official papers) that she was a certified guide, not some hitch-hiking Chinese hippie.

- This abandoned workers’ camp made a great place to camp. The buildings were slowly falling apart.

- We made ourselves at home for a night and even did a small wash.

- This pipe brought water from the distance mountains and filled an irrigation channel.

- An irrigation ditch gave us a good place to refill our water tank and take a hot shower.

- Satellite view of the Taklamakan Desert

Leave a Comment